But Bannerman, who was untrained, had never been to the States. Then there are Bannerman’s odd illustrations, which seem to reflect the influence of American racist imagery. First, there’s the name “Sambo,” which was “already in opprobrious use in the United States,” says Schreyer.

Sambo’s father scoops up the butter, his mother fries pancakes in it, and Sambo “eats a Hundred and Sixty-nine, because he was so hungry.” The End.

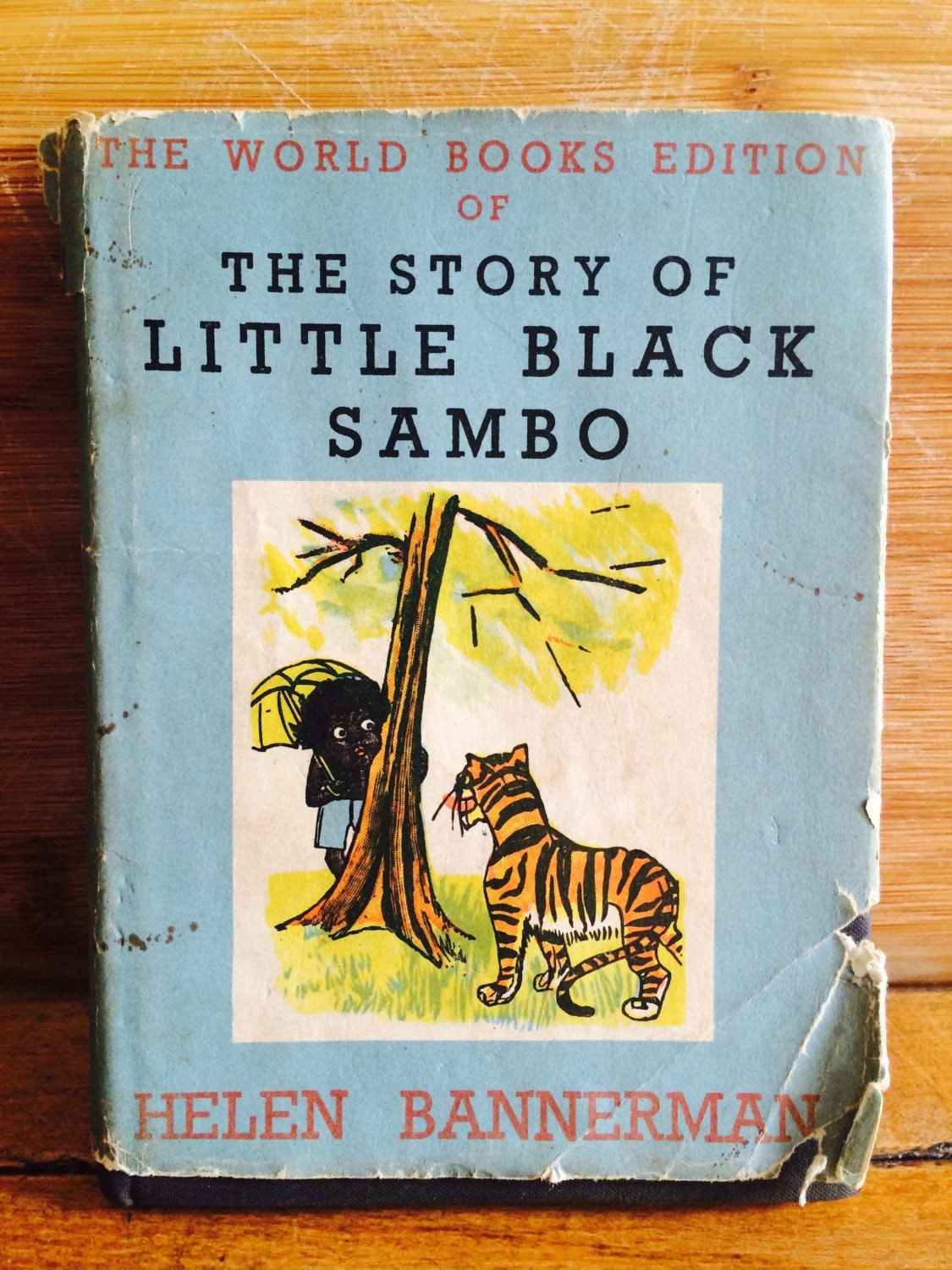

The tigers then fight over the clothes, chasing each other around a tree so quickly that they turn into melted butter. “And then wasn’t Little Black Sambo grand?”īut as he walks through the jungle, Sambo has to give away his fine clothing, piece by piece, to four tigers so they won’t eat him he manages to persuade them to take even the seemingly useless shoes (“You could wear them on your ears.”) and the umbrella (“You could tie a knot on your tail, and carry it that way.”). “It’s a story that children love,” says Alice Schreyer, director of Special Collections, “a classic children’s story.” In the original (if you have forgotten the details, as I had), Sambo gets a new outfit: a Red Coat, Blue Trousers, a Green Umbrella, and “a lovely little Pair of Purple Shoes with Crimson Soles and Crimson Linings,” in Helen Bannerman’s quirky capitalization. What is it about Little Black Sambo that inspires such discomfort? Why is it so widely considered racist? And if it’s racist, why has it endured? “It’s actually a really important donation to Special Collections, all these different editions of Little Black Sambo.” He nodded but looked unconvinced. When I told a colleague I was working on a piece about the book, I watched his eyes widen, and stay wide, as I babbled on, trying to contain the damage. It’s just that talking about it can create uneasy feelings. Of course, there is plenty to say, or at least ask, about Little Black Sambo. As the preface explains, “an English lady in India, where black children abound and tigers are everyday affairs,” had written and illustrated the story for her two young daughters during a long train journey. “There is very little to say about the story of Little Black Sambo,” reads the preface to the first American edition (1900), which, thanks to donors Barbara and Bill Yoffee, AB’52, I was able to hold in my hand at the Special Collections Research Center. The children’s book Little Black Sambo inspires uneasy feelings with its racist imagery, but a new library collection offers a rich trove for research into the story’s evolution.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)